The Washington Post has often referred to its Watergate reporting as the “first draft of history.”

What if the original draft was so revered that it is taught as a staple of modern journalism? What if the original journalism was so praised that no historian can contradict it? False history would result in our textbooks, and yes, our democracy would die in darkness.

Watergate Studies is witnessing this today as a new generation of historians is armed with hundreds and thousands of post-scandal books, documents, and articles. Instead of using these resources to improve Western society’s understanding of its most significant political scandal and its iconic journalism, historians do the opposite. The Watergate investigation had a common theme: “It’s not the crime, it’s the coverup.” This is why historians, who celebrate a Nixonian scandal being exposed, are actually covering up the widespread lies of the Washington Post. How is that possible?

This article will only cover one example. Remember that the most famous scene from All the President’s Men was Deep Throat bursting into the garage to shout, “Everyone’s lives are in danger!” This was the CIA’s concern not about Watergate’s implication, but rather its many years of “incredible,” domestic cover operations. These, he said, would be illegal and could land them in jail or lose their pensions. Deep Throat told Woodward that the CIA was involved with Watergate. He was also afraid that it would expose more illegality from decades ago, which is not possible without the tincture approval of the president.

If the Washington Post had published this tableau contemporaneously with Nixon’s death, attention would have been diverted from Nixon and to the rogue agency that infiltrated both the White House and the presidential campaign and had, for decades, been illegally acting, undermining citizens’ civil rights. The CIA’s focus would have led to the dark underbelly of the DNC, which was involved in the pathetic activity that enlisted the agency in this matter.

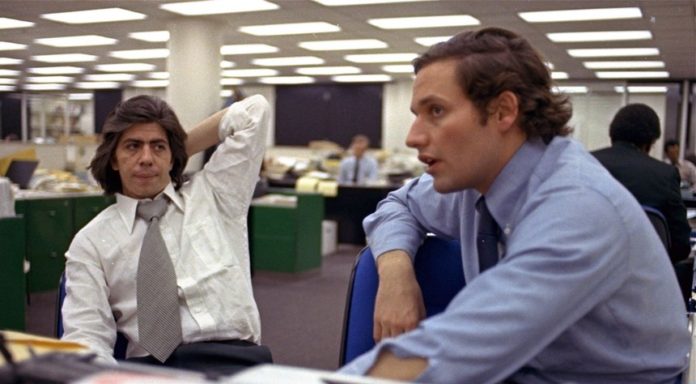

The Washington Post kept this disturbing, but highly significant episode secret from its readers. To their advantage, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, journalists, we’re unable to resist including this dramatic episode in their book and movie. However, they downplayed its true significance, claiming it was simply an overreaction by Deep Throat. Now that we know Deep Throat wasn’t an easily misunderstood amateur, Mark Felt, a savvy and experienced head of the FBI Watergate Investigation, is a responsible researcher who ignores Deep Throat at his peril.

Deep Throat at the May 1973 garage meeting recounted some facts likely from John Dean, the now-courting White House counsel. This included an Oval Office request ten months prior in which John Dean asked the CIA for permission to call the FBI on false pretenses regarding the “Mexican Money Trail” investigation. This had nothing to do with the warning that lives were at risk from the CIA, presumably the lives of witnesses who were pointing fingers at the agency.

Mark Felt was the FBI Watergate investigator in May 1973. He had known about the obstruction of the money trail for ten years and had also swatted it away like a housefly. This episode didn’t cause him any discomfort and wasn’t the reason for his agitation.

Garrett Graff’s impressive factual compilation Watergate: A New History reaches this conclusion. However, the author decides to keep his mouth shut rather than reveal that a. the CIA was involved in Watergate up to its eyeballs and b. the Washington Post deceived its readers by hiding this critical drama. This would have revealed both CIA Watergate Infiltration and its thuggish illegality from past years.

Graff made a lot of his extensive, detailed review of large troves of documents, including hundreds of tapes and documentaries, as well as thirty first-person accounts by protagonists. There are also thousands of hours of audio tapes from the White House. These recountings are corrected to the nth degree, spelling and dates included. This historian is certainly meticulous, the reader is led to understand. But when it comes to the dire warnings of Mark Felt, here is his questionable treatment:

… Felt appeared angry, worried, almost panicky. He spoke only for a few moments before he disappeared, warning Nixon about how Nixon tried to enlist the CIA to obstruct Watergate.

(Graff, Id. at p. 287.)

It is important to note that Graff focuses on a non-emergent, not frightening event that occurred months ago. This captures an incident in which the White House was guilty but the CIA innocent. This is the exact opposite of what Felt meant at the May 1973 garage meeting. It is likely that the author knew about credible suspicions that two potential whistleblower investigators were poisoned shortly afterward to induce heart attacks. A third witness fled to the FBI to report threats to his life before the meeting. What is the “out of nowhere” part? Hardly. He may be accused of violating Watergate’s lesson: Don’t hide the truth, but treat the incident as he did.

Graff, a young historian, might have been the first and only one to engage in historical shenanigans. If so, this example could be considered a simple exception, to be punished his peers. It isn’t an exception, as similar historical writing has been rewarded for 50 years. As we listen, watch, and listen to Watergate’s supposedly complete accounts, we need to ask the key questions. What entity was the principal agent of deceit? A White House that didn’t know or a Pulitzer Prize-winning paper that did? Watergate journalism’s global success has made it seem like the rest of academia and the media have been rendered unable to speak truthfully to Washington Post’s power. It seems that it has not taught the right lessons to journalism and academia.

Graff and other historians aren’t so much trying to reveal what happened in Watergate as they are continuing a fifty-year coverup in winking collaborations with the Washington Post.